Article from the OES Annual Report 2011

Anne Marie O’Hagan is a Charles Parsons Research Fellow, Hydraulics & Maritime Research Centre (HMRC), University College Cork - Ireland).

Introduction

Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP) is an essential tool for the sustainable development of maritime regions. It is intended to promote rational use of the sea by providing a stable and transparent planning system for maritime activities and users. Numerous definitions of MSP exist: in the European Union (EU) it is defined as a process that relates to planning and regulation of all human uses of the sea while protecting marine ecosystems. It is accepted in the EU that MSP focuses on marine waters under national jurisdiction. However, the geographic coverage of any MSP system will vary according to regional conditions. In principle, from an EU perspective, the MSP process does not include coastal management or planning of the land-sea interface, which is to be addressed through the implementation of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). Different terms tend to be used synonymously in current practice, for example, marine planning, ocean planning, and marine spatial planning. In the EU ‘Maritime’ Spatial Planning is preferred, as it is thought to capture the holistic, cross-sectoral approach of the process (COM(2008) 791 final). For this reason, the term Maritime Spatial Planning is used throughout this article.

This article initially outlines the policy basis for MSP in the EU, the principles for a common European approach and the status of MSP in individual Member States. The status is reviewed according to extant legislation, coordination of MSP and existing programmes, plans and projects that endeavour to implement MSP. While it is impossible to include a review of all national initiatives in this article, the approaches adopted by a selection of EU Member States are discussed and examples from key projects that focuson MSP, or aspects of it, are highlighted. To reflect the importance of MSP for marine renewable energy development, the article focuses on the application of MSP to marine renewable energy across Europe and, more specifically, how industry requirements are incorporated (or not) in existing MSP systems. The ocean energy sector is still developing and, as such, may have differing requirements to other sectors. The final section of the article considers other policy developments that are likely to influence the future development and functioning of MSP. As MSP is inextricably linked to Integrated Coastal Zone Management, the position of this in EU Member States is included.

Principles of Maritime Spatial Planning in the European Union

An Integrated Maritime Policy (IMP) for the European Union was published by the European Commission in2007 (COM(2007) 575 final). This acknowledged that there was increasing competition for marine space and that this was leading to both conflicts between existing users and deterioration of the marine environment. The IMP clearly recognised that everything relating to Europe’s oceans and seas is interlinked and, consequently, there is a need for an integrated approach to maritime governance and new tools to deliver this type of approach. Traditionally, management of marine resources and associated uses occurs on a sectoral basis with the existence of a management authority for almost every maritime activity. From previous experiences in resource management, it is known and accepted that such fragmented decision-making invariably results in conflicts of use, inconsistencies between sectors and in efficiencies. The Commission, through the IMP, therefore, sought to address this by applying the integrated management approach at every level, through the utilisation of both horizontal and cross-cutting policy tools. In this context, the IMP put forward maritime surveillance, Maritime Spatial Planning and [additional] data and information as three essential tools for integrated management.

Given the strong advocacy of MSP as the desired planning tool to be used for sustainable decision-making, the Commission felt it necessary to put forward a set of common principles to “facilitate the process in a flexible manner and to ensure that regional marine ecosystems that transcend national maritime boundaries are respected” (COM(2007) 575 final, p.6). A common approach was deemed necessary to ensure consistency. Competency for the design and implementation of MSP resides with individual Member Statesand not with the EU per se. This also explains why progress varies between Member States (see below). The Commission published their common principles in 2008 in a Communication entitled “Roadmap for Maritime Spatial Planning: Achieving Common Principles in the EU” (COM(2008) 791 final). In this Communication, the Commission put forward their rationale for the benefits of a European approach stating that, ultimately, the use and implementation of MSP will “enhance the competitiveness of the EU’s maritime economy, promoting growth and jobs in line with the Lisbon agenda… in line with ecosystem requirements” (p.3). The over-arching principle for MSP is the ecosystem approach, whereby human activities affecting the marine environment are managed in an integrated manner promoting conservation and sustainable use, in anequitable way, of oceans and seas (COM(2005) 504 final, p.5). This is complemented by ten supporting principles, presented in Box 1.

|

Box 1: European Union Principles for MSP (COM(2008) 791 final)

These principles were derived from existing approaches to MSP in Member States and other international examples that included research projects. Other legal instruments informed the creation of these principles. These include the United Nations (UN) Law of the Sea Convention, Regional Seas Conventions (e.g. OSPAR,HELCOM) and numerous EU legal instruments (e.g. Common Fisheries Policy, Water Framework Directive, Marine Strategy Framework Directive etc.). The Roadmap containing these principles is seen as “the first steps towards a common approach on MSP” (COM(2008) 791 final, p.11).

Status of MSP in EU Member States

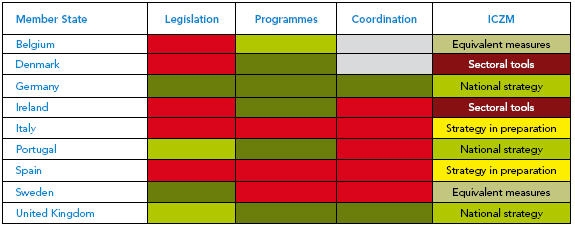

Not withstanding the strong policy base for MSP, implementation is taking place on a predominantly ad hoc basis. The EU member nations of the Ocean Energy Systems Implementing Agreement have implemented MSP differently (Table 1). Whilst few Member States have dedicated MSP legislation or an over-arching coordination authority, most have some form of programme or plan on MSP, a necessary first step in the MSP process. While such programmes and plans take a sectoral perspective, they have enabled initial debate on coexistence of maritime uses, conflicts between uses and problems with existing spatial management tools. This can inform the development of an appropriate MSP system, in line with the common principles above. Each Member State faces different challenges in developing an MSP system and it should be recognised at the outset that there is no single, correct approach to MSP. The approach taken will vary according to the size and nature of the maritime space, the types of activity and uses going on there, as well as the pertinent legal and institutional arrangements (MRAG/European Commission, 2008). As a result, a variety of mechanisms can be used to implement MSP, including specific regulations and zoning of sea areas. It is also important to stress that MSP is just one element of broader ocean management and should be viewed as a ‘strategic vision’ for a maritime area that is supported by a range of other policies, including sector specific policies (Ehler and Douvere, 2009)

Table 1: Status of MSP in EU Member States that are Members of the OES

With respect to legislation for, programmes on, and coordination of MSP dark green indicates that the Member State has sectoral elements in place. Bright green indicates that fully integrated elements are in place. Grey indicates that the status is unknown and red indicates that the element is not yet in place.The information presented in this table is adapted from Thetis, 2011.

Many States across Europe are just beginning to formulate an appropriate legal framework for MSP. This is complicated by competencies across governance levels in many EU Member States. In the case of Germany, for example, responsibility for MSP in the Territorial Sea (i.e. to the 12 nm limit) rests with the federal states (Lnder) as part of their regional planning functions. Beyond the Territorial Sea, in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (to 200 nm), MSP is the responsibility of the German Federal government. Specific legislation was enacted for spatial planning in the German EEZs of both the North Sea and the Baltic Sea in 2009. In Sweden, a Marine Environment Inquiry was appointed by the Government, in 2006, to explore ways in which their marine management could be improved. The report of the inquiry was released in June 2008 and found that it was time for a “third-generation environmental policy” that “must entail a holistic approach and full integration of environmental issues into all policy areas, stronger political leadership and, to a much greater extent, an international focus” (Ministry of the Environment, 2008). Despite this, no formal and integrated legal framework for MSP exists. Legislation for spatial planning of land, however, extends to the limit of the Territorial Sea. Belgium was among the first EU Member States to start implementing an operational, multiple-use planning system in its Territorial Sea and EEZ, through associated legislation, namely the EEZ Act of 1999 and the Marine Protection Act of 1999. In practice, these effectively provide for a zoning approach to regulate activities at sea rather than for a broader MSP process.

In contrast, the UK has adopted a new policy to deliver the provisions of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) in the United Kingdom12 through the enactment of the Marine and Coastal Access Act2009.13 This Act also establishes an integrated planning system for managing seas, coasts and estuaries, a new legal framework for decision-making as well as streamlined regulation and enforcement. The new marine planning system has three components: the Marine Policy Statement, Marine Plans and Marine Licensing. The Marine Policy Statement sets the general environmental, social and economic considerations that need to be taken into account in marine planning (Part 3, Chapter 1, sections 44 - 48). This Statement applies to all UK waters. Marine Plans must be consistent with the Marine Policy Statement and, ultimately, will indicate to developers the locations where (1) they can conduct their activities; (2) they can conduct their activities under certain restrictions or (3) their activities are unlikely to be considered appropriate (Part 3, Chapter 2, sections 49 - 54). Following the adoption of a marine plan, public authorities taking consenting or enforcement decisions must do so in accordance with those Marine Plans and the overarching Marine Policy Statement unless they can provide justification for doing otherwise (Part 3, Chapter4, sections 58 - 60).

Portugal has also been relatively progressive in implementing a legal framework for MSP. This stems from the publication of a National Ocean Strategy in 2006, which sought to integrate sectoral policies and define principles for both MSP and ICZM (Government of Portugal, 2006). As a response to this, work on the Plano de Ordenamento do Espaço Martimo (POEM), a Portuguese maritime spatial plan, began in 2008. The development of this plan consists of four stages, (1) characterisation studies and assessment; (2) provisional maritime spatial plan; (3) zoning plan and implementation programme; and (4) public consultation. The public consultation stage has recently ended and the final version of the plan is due for publication in the near future. In Denmark, Ireland, Italy and Spain work on the development of an appropriate MSP systemis just beginning.

In Denmark, for example, this has involved the creation of a working group, consisting of the relevant Danish authorities, which is tasked with presenting proposals for future practice in terms of MSP in Denmark (Danish Government, 2010). A number of pilot projects on MSP in Denmark also exist. Ireland is in the process of reforming its foreshore management regime and it is hoped that this will reflect the EU’s MSP principles (O’Hagan and Lewis, 2011). In Italy and Spain there is no integrated approach to MSP as yet, though there are some active projects which seek to apply MSP in specific locations.

Coordination of MSP systems also varies according to Member State. In some countries, there is a dedicated single management entity responsible for implementation of MSP. In the UK, for example, Part1 of the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 provided for the establishment of the Marine Management Organisation, which is tasked with implementing the new MSP system, the associated licensing regime, management of fishing fleet capacity and designation of Marine Protected Areas. In Portugal, any amendments to the POEM will require approval by a multi-disciplinary team, consisting of representatives from the relevant government ministries, Instituto Nacional da Água (INAG; Portuguese Water Institute) and four external consultants, including some university representatives (Calado et al., 2010). Generally, the constitutional system in each Member State will dictate their governance structure. Consequently, in States with complex governance structures, such as Belgium, Germany and the UK, the constitutional system will determine both the entity that has legislative capacity for elements of MSP and the level of government thathas primary competency over internal waters, the Territorial Sea, EEZ etc. (MRAG/European Commission,2008). Despite the governance model that exists, what is essential is that there is a framework to support MSP and facilitate integration amongst sectors. As a tool for improved decision-making, MSP must ensure that all stakeholders are included and can get involved in the process.

Plans, Programmes and Projects on MSP

From the brief outline above, it is clear that progress on MSP across the European Union varies significantly with few fully integrated and developed MSP systems. One way in which this is being addressed, both at EU and individual Member State level, is to begin the MSP process with a dedicated MSP programme, or pilot demonstration, at specific locations, often where a range of maritime uses exist. Such initiatives can be instigated solely at national level but more commonly take a regional or pan-European approach, reflective of the approach suggested in the IMP, and as such can be funded under various EU research programmes such as FP7, Intelligent Energy Europe and INTERREG. Table 2 presents a selected sample of such projects, paying particular attention to those that have a marine renewable energy focus.

| NAME | AIMS AND OBJECTIVES | WEBSITE |

| INTERREG III BALANCE: BalticSea Management: Nature Conservation and Sustainable Development of the Ecosystem through Spatial Planning | The project aims to develop transnational MSP tools and an agreed template for marine management planning and decision-making. It is based on 4 transnational pilot areas demonstrating the economic and environmental value of habitat maps and MSP (through 2 zoning plans). The tools and zoning plans integrate biological, geological and oceanographic data with local stakeholder knowledge | http://www.balance-eu.org/ |

|

INTERREG IV BaltSea Plan: Towards a Spatial Structure Plan for Sustainable Management of the Sea |

With a learning-by-doing approach, BaltSeaPlan will attempt to overcome the lack of relevant legislation in most Baltic Sea Region countries for MSP. The project developed pilot plans for 8 demonstration areas around the Baltic Sea and has also advanced methods, instruments and tools and data exchange necessary for effective maritime spatial planning. | http://www.baltseaplan.eu/ |

|

FP7 COEXIST: Interaction in Coastal Waters: A Roadmap to Sustainable Integration of Aquaculture and Fisheries |

COEXIST is a broad, multidisciplinary project which will evaluate competing activities and interactions in European coastal areas. The ultimate goal is to provide a roadmap to better integration, sustainability and synergies among different activities in the coastal zone. Six casestudy areas are included in the project. | http://www.coexistproject.eu/ |

| INTERREG III GAUFRE: Towardsa Spatial Structure Plan for Sustainable Management of the Sea | The main aim of the project is the delivery and the synthesis of scientific knowledge on the use and possible impacts of use functions. Consequently, a first proposal of possible optimal allocations of all relevant use functions in the Belgian part of the North Sea (BPNS) will be formulated. | http://www.vliz.be/projects/ gaufre/index.php |

| FP7 KnowSeas: Knowledgebased Sustainable Management for Europe's Seas |

The overall objective of the project is to provide a comprehensive scientific knowledge base and practical guidance for the application of the Ecosystem Approach to the sustainable development of Europe’s regional seas. It will be delivered through a series of specific subobjectives that lead to a scientifically-based suite of tools to assist policymakers and regulators with the practical application of the Ecosystem Approach to various sectors. | http://www.knowseas.com/ |

| EU Preparatory Action (IMP) MASPNOSE | The project will explore the possibilities for cross-border collaboration in maritime spatial planning in the North Sea and will build on other projects and initiatives that are already looking at integrating spatial information and planning. | https://www.surfgroepen.nl/sites/CMP/ maspnose/default.aspx |

| FP7 MESMA: Monitoring and Evaluation of Spatially Managed Areas |

This project aims to produce integrated management tools (concepts, models and guidelines) for monitoring, evaluation and implementation of Spatially Managed Areas (SMAs). The project results will support integrated management plans for designated or proposed sites with assessment methods based on European collaboration. | http://www.mesma.org |

| FP7 ODEMM: Options for Delivering Ecosystem-Based Marine Management |

The aim is to develop a set of fully-costed ecosystem management options that would deliver the objectives of the MSFD, the Habitats Directive and the IMP. The key objective is to produce scientifically-based operational procedures that allow for a step by step transition from the current fragmented system to fully integrated management. | http://www.liv.ac.uk/odemm |

| EU Preparatory Action (IMP) PlanBothnia | The project, coordinated by the HELCOM Secretariat, will test MSP in the Bothnian Sea area as a transboundary case between Sweden and Finland. Partners provide background material on relevant human activities and natural features as well as draft material for plans for the Bothnian Searegion. This material will be considered in five dedicated transboundary planning meetings. | http://planbothnia.org |

| INTERREG III PLANCOAST | The aim is to develop the tools and capacities for effective integrated planning in coastal zones and maritime areas in the Baltic, Adriatic and Black Sea regions. PlanCoast pilot projects formed the basis for recommendations at local and national level on how to implement, adapt and further develop the ICZM and MSP in each partner country. | http://www.plancoast.eu |

| INTERREG III POWER: Pushing Offshore Wind Energy Regions | The central aim of POWER is to unify North Sea regions, to learn from each other, to set up common strategies overcoming economic changes, to respond to new educational needs and thereby give a positive impetus to continuing sustainable development of the region. | http://www.offshore-power.net |

| EACI/IEE SEAENERGY 2020 | The project will formulate concrete policy recommendations on how best to deal with MSP and remove MSP obstacles that hinder the deployment of offshore renewable energy. It will provide policy recommendations for a more coordinated approach to MSP and larger deployment of marine renewables (wind, wave, tidal). | http://www.seanergy2020.eu |

| EACI/IEE WINDSPEED: Spatial Deployment of Offshore WindEnergy in Europe | Windspeed aims to assist in overcoming existing obstacles to deployment by developing a roadmap defining a realistic target and development pathway up to 2030 for offshore wind energy in the Central and Southern North Sea. This includes delivering a decision support system (DSS) tool using geo-graphical information system (GIS) software. This will also facilitate the quantification of trade-offs between electricity generation costs from offshore wind and constraints due to non-wind sea functions and nature conservation, thereby assisting policy makers in terms of allocating space for the development of offshore wind the Central and Southern North Sea. | http://www.windspeed.eu |

The deliverables from many of the above mentioned projects will assist in the development of more effective national and regional MSP systems. This is particularly true of projects that have a specific sectoral or industry focus, such as renewable energy, or projects that consider the potential for conflict between actors, for example, fisheries and offshore wind energy.

Application of MSP to Marine Renewable Energy

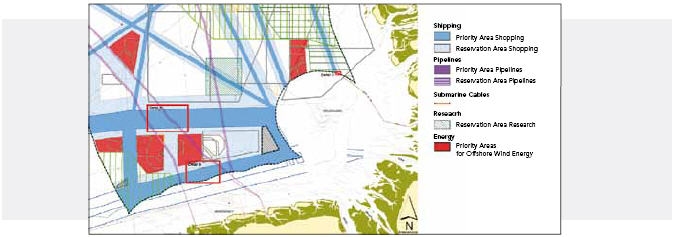

Inclusion of marine renewable energy requirements in MSP systems varies not only according to location but also according to the status of the industry in that country. In Germany, for example, dedicated work on MSP was triggered by the economic interest in developing offshore wind energy, which was necessary to achieve the Government’s emission targets (MRAG/European Commission, 2008). To secure the scale of investment needed for such large scale projects, a stable and predictable planning framework was required. MSP was viewed as the process which could help identify and allocate areas to certain activities and thus contribute to expediting the decision making process. Priority areas for offshore wind energy development in the German EEZs of both the North Sea and the Baltic Sea were subsequently zoned (Figure 1). Belgium has taken a similar ‘zoning’ approach and legally designated a 270 km area for offshore wind projects (total capacity of 2,000 MW).14 Whilst Denmark does not have an established MSP system in place, 23 sites were pre-selected for offshore wind energy development as far back as 2007 (Danish Energy Authority, 2007).

Figure 1: Extract from Spatial Plan Map for the German EEZ of the North Sea (BMVBS, 2009)

It should be emphasised here that zoning of activities/areas is one of a number of management mechanisms which may be introduced in a Marine Spatial Plan to help achieve the overall objectives of the MSP system. Technically, zoning can be described as a management tool for spatial control of activities with defined activities, permitted or prohibited from specified geographic locations (Gubbay, 2005). Zoning can separate conflicting activities or indeed give a particular sectoral interest exclusive use of an area of sea, as is the case in the above mentioned examples for offshore wind energy development. Generally, if an area is zoned fora particular use, that use will require the granting of a consent or licence15 so that a dedicated space can be allocated. A consent or licence, therefore, is the mechanism by which the overall objectives of MSP are translated into the rights and responsibilities of individual users. Obviously, it is also essential that an MSP system is sufficiently flexible to take new information and, in the context of ocean energy, new technology types into account. An overly-prescriptive MSP system, for example, could restrict future developments and nnovation. For this reason, an adaptive management approach is inherent in many MSP systems and any supporting Plan will set an explicit timeframe for review. The incorporation of adaptive management principles into MSP also allows the potential for coexistence of industries to be explored. It may bepossible for certain fishing activities to co-exist with marine renewables developments, for example, fishing involving potting techniques.

Given the current status of ocean energy development in the European Union, very few existing maritime spatial plans currently include a dedicated area for ocean energy development. One exception to this is in Scotland and relates to the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters and the MSP approach taken by Marine Scotland. This area has significant ocean energy resources and is also of high environmental quality. The area is host to a range of other uses and sectors such as fishing and shipping. Consequently, there was a need to examine how future ocean energy development could progress in a manner that avoided conflict with those users. MSP was the obvious solution of choice, but the legislative framework setting out the requirements and content of regional marine plans was not yet in place. A de facto Marine Spatial Plan Framework (MSPF) was put in place, which sets out a process for the development of future plans, covering the areas from the mean high water mark out to the limit of the Territorial Sea (12 nm) (Scottish Government/Marine Scotland, 2010). This Framework consists of a document that contains information on different uses of the seas, how these uses may impact on each other and ultimately aims to set out the process for developing the future, over-arching MSP System. The Framework document is complemented by a Regional Locational Guidance document, which provides guidance and advice to marine renewable energy developers and other stakeholders on the siting of wave and tidal developments in the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters (Scottish Government/Marine Scotland, 2010).

Elsewhere, test sites and pilot demonstration zones are usually close to shore in the coastal zone, which is often outside the geographic scope of any existing MSP system. As yet, the latter applies primarily to territorial seas and EEZs, with nearshore coastal planning being the responsibility of the adjoining local authority or regional government. This boundary varies according to jurisdiction. In Britain and Ireland, for example, planning powers end at the low water mark and high water mark, respectively. In the Scandinavian countries, local governments have planning powers extending up to three miles offshore. This is of relevance to ocean energy development, as developments have the potential to straddle a number of maritime jurisdictional zones. A probable implication of this is that a number of regulatory bodies will be involved in the consenting process. MSP should, therefore, address this issue by providing an integrated planning framework.

More established maritime sectors and uses are subject to more mature management regimes and, as their needs are well known and documented, it is arguably easier to reflect their needs in a MSP system. Newer industries, such as ocean energy, have not reached this stage yet but still require the predictable and transparent planning system that MSP seeks to deliver. For this reason, it is essential that the needs ofthe industry are made known to those tasked with developing MSP in their region.

Key considerations include:

Other Policy Developments with Implications for MSP Implementation

The Marine Strategy Framework Directive (2008/56/EC) was adopted by the European Commission in June 2008. This aims to achieve ‘Good Environmental Status’ (GES) of the EU’s marine waters by 2020 and to protect the resource base upon which marine-related economic and social activities depend. This Directive therefore enshrines the ecosystem approach in a legislative instrument. Accordingly, the MSFD will deliver the environmental pillar of the IMP. Under the Directive, Member States must develop a strategy for their marine waters. This strategy must contain a detailed assessment of the state of the environment, a definition of ‘GES’ at regional seas level and the establishment of clear environmental targets and monitoring programmes. Member States must determine a set of characteristics for GES on the basis of eleven qualitative descriptors listed in Annex I of the Directive. These descriptors are presented in Box 2.

|

Box 2: Qualitative Descriptors for Determining ‘Good Environmental Status’ (Annex I, MSFD)

A number of these descriptors could have significant implications for future marine renewable energy developments. Following an initial characterisation, Member States are required to identify the measures which need to be taken in order to achieve or maintain GES in their marine waters. According to Annex VIof the Directive, programmes of measures can include, amongst others, spatial and temporal distribution controls: management measures that influence where and when an activity is allowed to occur. Theoretically, therefore, the MSFD could contribute to the implementation of MSP at Member State level.

To a certain extent, this has been the experience in Spain, for example, where the legislation transposing the requirements of the MSFD into national law specifically lists MSP as one of the measures that can be adopted to achieve or maintain GES (Surez de Vivero and Rodrguez Mateos, 2012).

MSP is inextricably linked to Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). A review of the need for a new or revised instrument on ICZM in the EU is currently underway. Given these linkages, the review is being carried out in conjunction with an assessment of possible future action on MSP. The Commission will put forward a range of proposals as a follow-up to the EU ICZM Recommendation, in conjunction with an assessment of possible future action on Maritime Spatial Planning, as appropriate, by the end of 2011.

While it is not certain at this time what format the proposals will take, a new Directive on MSP may be one of the proposals. This would provide a common framework for MSP in Member States of the EU, making MSP mandatory, while simultaneously leaving Member States free to decide on how to implement the process. If there is a Directive on MSP, there may also be a separate, but related, Directive on ICZM.

CONCLUSION

Maritime Spatial Planning will have significant implications for the development of marine renewables generally and the ocean energy sector in particular. Economic development and marine environmental protection have an equal weighting in the EU’s Integrated Maritime Policy and both elements are either already specifically addressed in legislation or will be in the near future. This means that it is essential for the ocean energy industry to engage fully in the Maritime Spatial Planning process to ensure that conflicts are minimised and that the industry can progress in a sustainable manner. From an industry perspective, it is essential that research is undertaken to understand the extent to which ocean energy developments can be deployed and co-located with other users of the sea. This could help lessen the need for ‘exclusion zones’ within MSP systems.

As a key player in the advancement of ocean energy, the Ocean Energy Systems Implementing Agreement (OES) is in a unique position to encourage device and project developers to involve themselves in the debates and processes surrounding development of Maritime Spatial Planning systems in different jurisdictions. The European Commission recognized that stakeholder participation will significantly raise the quality of MSP(COM(2008) 791 final). Developers already have a wealth of tacit knowledge from their experiences of deploying devices. They know what has worked well and where. This type of knowledge will help inform the creation of an MSP system that is both fully reflective of the needs of the industry and will also enlighten other industries as to the specific requirements of the ocean energy sector. The OES should promote this active involvement of the sector, as it is an essential criterion for progress and acceptance of MSP.

References

BMVBS [Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development]. Spatial Plan for the German Exclusive Economic Zone in the NorthSea - Text and Map sections. Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency, Hamburg. 2009. Available from:

http://www.bsh.de/en/Marine_uses/Spatial_Planning_in_the_German_EEZ/index.jsp

Calado H, Ng K, Johnson D, Sousa L, Phillips M, Alves F. Marine spatial planning: Lessons learned from the Portuguese debate. Marine Policy2010; 34: p.1341-1349.

Danish Energy Authority. Future Offshore Wind Power Sites - 2025. The Committee for Future Offshore Wind Power Sites. 2007.

Danish Government. An Integrated Maritime Strategy. Danish Maritime Authority, Copenhagen, Denmark. 2010. Available from:

http://www.dma.dk/SiteCollectionDocuments/Publikationer/SFS-Samlet-maritim-strategi_3UK.pdf

Ehler C, Douvere F. Marine Spatial Planning: a step-by-step approach toward ecosystem-based management. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and Man and the Biosphere Programme. IOC Manual and Guides No. 53, ICAM Dossier No. 6. UNESCO,Paris. 2009.

Government of Portugal. National Ocean Strategy. Resoluo do Conselho de Ministros no.163/2006. Dirio da Repblica, 1.a Srie, no.237, Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 12 Dezembro 2006 [in Portuguese]. Lisboa, Portugal. 2006.

Gubbay S. Marine Protected Areas and Zoning in a system of Marine Spatial Planning - A discussion paper for WWF-UK. 2005.

Ministry of the Environment. Better management of the marine environment. The Marine Environment Inquiry. Swedish Government OfficialReport SOU 2008:48. Stockholm, Sweden. 2008.

MRAG/European Commission. Legal Aspects of Maritime Spatial Planning; Framework Service Contract No. FISH/2006/09 – LOT2 for DG Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, European Commission. 2008.

O’Hagan AM, Lewis AW. The existing law and policy framework for ocean energy development in Ireland. Marine Policy 2011; 35: 772-783,doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2011.01.004.

Scottish Government/Marine Scotland. Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters Marine Spatial Plan Framework and Regional Locational Guidance for Marine Energy. Final Report. Marine Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland. 2010. Available from:

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/marine/marineenergy/wave/rlg/pentlandorkney/mspfinal

Surez de Vivero JL, Rodrguez Mateos JC. The Spanish approach to Marine Spatial Planning: Marine Strategy Framework Directive vs. EUIntegrated Maritime Policy. Marine Policy 2012; 36: p.18-27, doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2011.03.002.

Thetis. Analysis of Member States progress reports on Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). A report for DG Environment, European Commission. 2011. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/iczm/pdf/Final%20Report_progress.pdf

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon works supported by the Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) under the Charles Parsons Award for Ocean Energy Research (Grant number 06/CP/E003).

_______________

12 The UK, in this context, refers only to England and Wales. The Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 and proposed legislation in Northern Ireland wil introduce new marine planning systems in those jurisdictions.

13 Formerly known as the Marine Bill.

14 Royal Decree of 17 May 2004

15 Different jurisdictions use different terms for this, e.g., consent, permission, licence, lease, permit etc. The term to be used will be defined by the applicable legislation. In Ireland, for example, under foreshore legislation, a licence is granted for short-term, non-exclusive use/occupation, whereas a lease is granted for long-term, sole use/occupation.